The last presidential election cycle made it abundantly clear that something about our way of life does not “work.” After voting for change in 2008 and getting more of the status quo over the next eight years, furious voters from both parties decided to look outside the establishment for leadership.

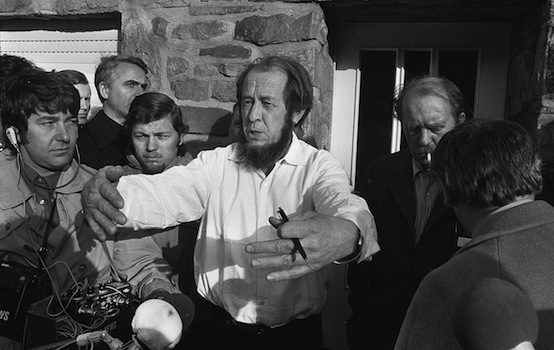

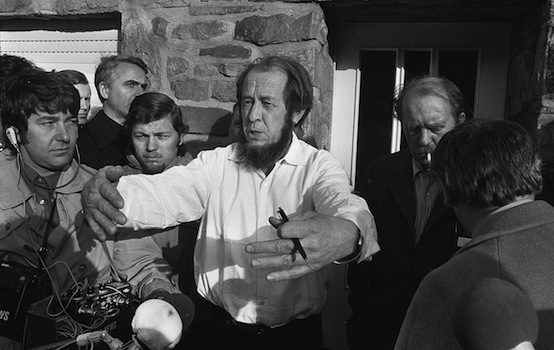

So what exactly are we feeling right now? Perhaps it might be useful to take a trip to the past, 40 years ago to be exact. On this day in 1978, Russian writer Aleksander Solzhenitsyn delivered a commencement speech to Harvard University graduates, entitled “A World Split Apart.“ Not surprisingly, his fears about the sustainability of American society and culture still resonate today—though he offers little solace that any of it can be easily resolved.

While the country reeled from its recent losses in Vietnam and saw little inspiration coming the Carter administration, the gathered graduating class of Harvard ‘78 gathered—America’s elite—probably expected the former Gulag inmate to praise and reaffirm American exceptionalism and democratic ideals at the height of the Cold War.

To their disappointment, however, Solzhenitsyn had no such intentions. After noting at the outset that trust is not often “sweet” but “bitter,“ he said “a measure of truth is included in my speech today, but I offer it as a friend, not as an adversary.”

Not to put a finer point on it, Harvard Magazine recalled in 2011 that the ‘The Exhausted West,’ delivered in Russian with English translation under overcast skies, chastised the arrogance and smugness of Western materialist culture and exposed the adverse effects of some of those achievements that Western democracies had long prided themselves upon.”

In doing so he further underscored that the true divide between what seemed to be two world superpowers was much deeper and more complex than simply capitalism-versus- communism—a context sorely missing in the American Cold War reality, whether it be politics, news, film, or higher education.

The Nobel Prize winner indeed trained most of his fire on the West (“since my forced exile in the West has now lasted four years and since my audience is a Western one”), on its early colonization of other worlds, “not only without anticipating any real resistance, but usually with contempt for any possible values in the conquered people’s approach to life. It all seemed an overwhelming success, with no geographic limits. Western society expanded in a triumph of human independence and power.”

But there were limits, and in 1978: “it is difficult yet to estimate the size of the bill which former colonial countries will present to the West and it is difficult to predict whether the surrender not only of its last colonies, but of everything it owns, will be sufficient for the West to clear this account.”

Meanwhile in the West, the bill of The Enlightenment, and of humanism and unbridled individual liberty was also coming due in the 20th Century.

“Destructive and irresponsible freedom has been granted boundless space. Society has turned out to have scarce defense against the abyss of human decadence, for example against the misuse of liberty for moral violence against young people, such as motion pictures full of pornography, crime, and horror. This is all considered to be part of freedom and to be counterbalanced, in theory, by the young people’s right not to look and not to accept.”

He blamed the Western ruling class for lacking “civic courage,” leaving society, essentially, with so much freedom and material gain that they lost the ideals for the “common good” or the spiritual nourishment that served as motivating factors, if not necessary guideposts, for liberty in the first place.

Every citizen has been granted the desired freedom and material goods in such quantity and in such quality as to guarantee in theory the achievement of happiness, in the debased sense of the word which has come into being during those same decades. (In the process, however, one psychological detail has been overlooked: the constant desire to have still more things and a still better life and the struggle to this end imprint many Western faces with worry and even depression, though it is customary to carefully conceal such feelings. This active and tense competition comes to dominate all human thought and does not in the least open a way to free spiritual development.)

In the pre-modern worldview that ended with the Renaissance, mankind was inherently evil and had to be made better. But following these harsh times, he noted, “we turned our backs upon the Spirit and embraced all that is material with excessive and unwarranted zeal.”

Solzhenitsyn claimed that when “modern Western states were created, the principle was proclaimed that governments are meant to serve man and man lives to be free and to pursue happiness.” No longer was the world God’s domain, the “world belongs to mankind and all the defects of life are caused by wrong social systems, which must be corrected.”

Solzhenitsyn reminded his audience that the American experiment at its founding understood “all individual human rights were granted on the ground that man is God’s creature. That is, freedom was given to the individual conditionally, in the assumption of his constant religious responsibility.” Never was the historical idea of freedom or pursuit of happiness interpreted as satisfying “instincts or whims”.

Having been exiled from the USSR in 1974 for publishing the Gulag Archipelago, which shockingly detailed the Soviet prison camp system, Solzhenitsyn had the opportunity to study the United States in person and summarized our society’s organization as completely based on what he characterized as “the letter of the law.” The “limits of human rights are determined by a system of laws” and “any conflict is solved according to the letter of the law and this is considered to be the supreme solution.” While he admitted,“I have spent all my life under a Communist regime and I will tell you that a society without any objective legal scale is a terrible one indeed,” the western situation created an atmosphere “moral mediocrity” and “paralyzed man’s noblest intentions.”

The legalistic nature of society, devoid of a strong religious foundation, he said, was not conducive to mankind’s higher potential and could not stem or control human decadence and selfish impulses.

“Voluntary self-restraint is almost unheard of: everybody strives toward further expansion to the extreme limit of the legal frames.”

A slavophile deeply distressed by the totalitarian USSR, Mother Russia was not spared by her native son for her embrace of humanism which then led to socialism, and eventually, communism. Ending his speech, the former Gulag inmate tied his visions together:

“We have placed too much hope in political and social reforms, only to find out that we were being deprived of our most precious possession: our spiritual life. In the East, it is destroyed by the dealings and machinations of the ruling party. In the West, commercial interests suffocate it. This is the real crisis. The split in the world is less terrible than the similarity of the disease plaguing its main sections.”

With the dissolution of the USSR and the end of the Cold War one superpower crumbled and the freedom loving United States still stood. The Western world cheered the triumph of freedom and markets. The final battle between world ideologies was over. The future would be democracy across the world. World peace was at hand.

But was our victory due to the merit of our system or simply the collapse of Soviet socialism with the arrow of time, the final proof that communism simply doesn’t work? After all, the United States never directly fought the USSR in a military campaign. Nuclear weapons kept the peace.

Solzhenitsyn’s opinion fell into the latter. Russia’s experiment in totalitarian communism lasted about 70 years, a small blink of time in Russia’s rich history. The American experiment in life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness is about to turn 242 years old.

In the Bible the number 40 represents a time of trial and testing, or even a probationary period. He added:

I hope that no one present will suspect me of expressing my partial criticism of the Western system in order to suggest socialism as an alternative. No; with the experience of a country where socialism has been realized, I shall not speak for such an alternative…

But should I be asked, instead, whether I would propose the West, such as it is today, as a model to my country, I would frankly have to answer negatively. No, I could not recommend your society as an ideal for the transformation of ours. Through deep suffering, people in our own country have now achieved a spiritual development of such intensity that the Western system in its present state of spiritual exhaustion does not look attractive. Even those characteristics of your life which I have just enumerated are extremely saddening.

On the anniversary of his speech it is worth examining the American system after many trials and tests over the last 40 years. Where do we stand today?

Materially speaking, there is a lot to be proud of.

Our supermarkets are stocked to the brim, abundant and cheap fossil fuels power our cars and homes, 4 (soon to be 5) G networks keep us connected at all times, diseases have been eradicated, and any consumer good our hearts desire is at the touch of our fingers with Amazon Prime.

But despite these luxuries that make America the envy of the free world, the average citizen has had second thoughts. Domestically we are facing racial and economic tensions, a demoralized middle class, record deficits, and a polarized electorate to name a few. Notable writers at The American Conservative have commented on our pathologies, and the shift from democracy to nationalism.

40 Years after a World Split Apart, as Americans search for answers to our present state of dissatisfaction, our leaders and citizens would be wise to heed the central theme of Solzhenitsyn’s message:

“It is time, in the West, to defend not so much human rights as human obligations.”

Jeff Groom is a former Marine officer. He is the author of American Cobra Pilot: A Marine Remembers a Dog and Pony Show (2018).

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com

0.00 (0%) 0 votes