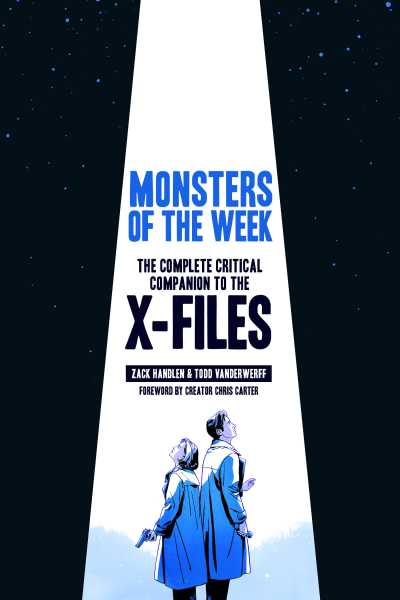

The following is an excerpt from Monsters of the Week: The Complete Critical Companion to The X-Files, by Vox.com critic at large Todd VanDerWerff and Zack Handlen. Monsters of the Week is available now.

The history of television can be told through certain shows, as surely as it can be told through certain personalities or events.

Think of I Love Lucy, discovering a way to produce very good TV comedy with speed and exactitude. Or of The Sopranos, paving the way for an era of morally complex dramas starring men (yeah, almost always men) who rarely worried about doing the right thing. TV as a medium, maybe even more than film or literature, tends to define itself in terms of landmark programs. Shows are seen and assessed in terms of their influences, or in terms of what “era” they roughly fell into.

This is, of course, an oversimplification. No TV series arrives without precedent, and no show so completely defines an era that every other contemporaneous show lives in its shadow. But that oversimplification still helps people who think about television figure out how to classify various artistic movements within a medium that moves quickly and often responsively to events within both the medium itself and the world at large.

But this mode of thinking means that the influence The X-Files had on our modern television era has been largely ignored. The X-Files aired in an awkward time, between other more obviously notable shows. In an age when most other big TV programs were workplace ensemble dramas that discussed the major issues of the day (see: ER, NYPD Blue, Chicago Hope, Law & Order), The X-Files was one part coolly deliberate throwback and one part forward-looking masterpiece. It had bad episodes and good episodes, and its overarching storyline about an alien conspiracy to take over the Earth eventually stopped making sense. But it was the rare series that could follow up an episode that barely worked with an episode that made it seem like the best show on television.

If nothing else, week after week, it sent its two central FBI agents out into a scarier, more cinematic America than had ever been seen on the small screen. Mulder and Scully were always in search of some dark secret, some monster that needed stopping. It was a lonely series, as much about an inexorably changing country and world as it was about those terrifying creatures. It was about a moral reckoning with what the United States had done to win the Cold War. And, yes, it was about the monsters themselves, ripping flesh from bone, spattering blood, and, in the process, becoming rich metaphors for a nation’s evolution.

Let’s step back, though, just for a second, from what you might think you know about The X-Files — from the flashlights cutting through darkness and the aliens arriving on Earth; from the near romance between Mulder and Scully and the massive commercial and critical success; from the very idea of horror on television. In order to talk about this show as a TV show, rather than a series of images and moments, we have to look at the shows that influenced it, and the ways it influenced television in turn.

The X-Files was most directly inspired by three core shows

If you look across the current programming dial, you’ll see shows that live in the shadow of The X-Files and still other shows that followed its spooky trail into different corners of the woods. The X-Files is that rare show that seems to exist both in the time it aired and in the present. (The show originally ran between 1993 and 2002, with one movie arriving in 1998; another movie arrived in 2008, and two follow‑up seasons aired in 2016 and 2018.) It is, beyond all reason, timeless, despite being perhaps the ultimate TV show of the 1990s.

If we want to understand how and why The X-Files was able to transcend, against all odds, we need to look at both its forebears and the ways the show itself (sometimes subtly) altered television.

There are three core television shows from which The X-Files drew inspiration. The first is Kolchak: The Night Stalker (1974–75). The X-Files creator Chris Carter has frequently pointed to this one-season series about a monster-hunting newspaper reporter as having a tremendous influence on his show, so it makes sense to start its lineage here. But I would posit that the influence of Kolchak extends beyond the fact that its hero tracked down monsters and ghouls haunting the night. Beyond these trappings, Kolchak figured out a format through which horror on television could be effective, long before The X-Files came along.

Here’s the problem with horror on TV: Horror requires the release of tension, often via the catharsis of gore. The monster needs to strike, or the hero needs to vanquish it. The genre needs viewers to believe that the characters are, in some way, in palpable danger. TV, on the other hand, requires a reversion to the status quo. If Fox Mulder and Dana Scully are our main characters, we know they won’t die, because if they did, we might stop watching the show. Both Kolchak and The X-Files put their main characters in danger, but rarely did the audience actually fear for them. That lack of suspense would seem to defeat the purpose of horror.

Yet Kolchak saw that horror could exist on the margins of a series. Guest stars could be killed off, and Kolchak could live on, burdened with the existential horror that all was not as it seemed, that the day-to-day thrum of life carried within it something unspeakable and brutal.

When viewed through the eyes of the guest stars, Kolchak was, indeed, a horror series, about unfortunate and fatal encounters with unlikely beings. But viewed through the eyes of Kolchak himself, it became more of a cop drama, with cases of the week and the slow-building weight of a job that sat heavily in his soul.

The X-Files would follow Kolchak’s lead and be more of a cop show than a straight horror drama. What’s more, The X-Files was a ’70s cop show, with every episode dropping its protagonists into a new, fascinating milieu somewhere in the middle of nowhere America. Rather than being stationary, our heroes, Mulder and Scully, traveled all over the country, finding new monsters to hunt. Eventually, the horror became existential for them too. They knew the secrets, but nobody would believe them. The darkness was everywhere, but nobody cared.

The second series to prove fruitful for the creation of The X-Files was Moonlighting (1985–89). This five-season ABC comedy/drama about two bantering detectives, one a guy’s guy and the other a girl’s girl, might seem to have most influenced the dynamic at the core of The X-Files. The romantic tug-of-war between Moonlighting’s leads eventually resolved in the two hooking up late in the third season, only for the show to go off the rails soon thereafter. (The downturn in the show’s quality has frequently been blamed on the two leads hooking up. I would argue against that interpretation and believe that the hook‑up was the right call for that show, but the lesson Moonlighting’s ratings drop passed on to other TV shows, nevertheless, was almost always about not shooting your sexual chemistry in the foot by consummating it.)

To be sure, the white-hot chemistry between Mulder and Scully (or, perhaps more accurately, actors David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson) and the series’ seeming reluctance to consummate that chemistry made it seem as if the show had taken several pages from the Moonlighting playbook.

But The X-Files borrowed almost as much from Moonlighting’s tone as it did from its central pairing. Like the earlier series, The X-Files would expand its template to the breaking point. Moonlighting offered episode-length riffs on Shakespeare or film noir; The X-Files lovingly paid homage to old Universal horror movies and Alfred Hitchcock’s real-time filmmaking experiment Rope.

Moreover, neither series was entirely comfortable as a “drama.” Because The X-Files had to have some sort of monster every week, it had less leeway to suddenly burst into sparkling screwball comedy, but it was constantly aware of its own ridiculousness. The longer it ran, the more The X-Files took sidelong swerves into absurdism.

The third show that left an indelible mark on The X-Files was Twin Peaks (1990–91), the show that most immediately preceded it. (There was a follow‑up season of Twin Peaks in 2017, too, but for obvious reasons, that couldn’t have influenced The X-Files.) In the initial spate of reviews for The X-Files’ pilot and first season, most critics pointed to David Lynch and Mark Frost’s remarkable, eerie drama as a clear influence.

Especially in the early days, it’s easy to see why: Twin Peaks sent an FBI agent into the middle of small-town America to discover the horrors at its center; it was filmed in the Pacific Northwest and, thus, looked like no other show on the air; and it broadcast some of the scariest sequences ever put on television. (Especially anything to do with the greasy, long‑haired demon BOB, who would turn up in dream sequences just to make everything go south.)

But the element The X-Files adopted most from Twin Peaks wasn’t its shooting location or a sense of horror. It was, instead, a willingness to take its time with the look of a series, to come up with visual ways to tell its stories. The scares in The X-Files arrive, often, from looking at some everyday location or item in just the right way to ask what darkness could be lurking within it, just as Twin Peaks destabilized reality by twisting up the primetime soap and the small-town drama with nightmare logic.

The X-Files, which calmly and carefully closed a new case every week, couldn’t be more structurally different from the open-ended, intentionally obtuse Twin Peaks. But the two looked so similar all the same that it wouldn’t have seemed all that out of place had the two shows cross-pollinated, and Mulder and Scully turned up in Washington State to solve the death of Laura Palmer. (The X-Files even used a number of Twin Peaks alumni over the course of its run; notably, David Duchovny played a minor role in Twin Peaks’ second season as DEA Agent Denise Bryson.)

So: Now that we know from whence The X-Files emerged, let’s look at the ways it shaped the modern TV landscape.

The X-Files had an enormous influence on the TV of today

The way I see it, The X-Files invented modern television in five major ways.

First, our modern crime dramas are usually just X-Files that have jettisoned the supernatural elements. Late in The X-Files’ run, CBS launched CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (2000–15), a science-obsessed, agreeably nerdy show about lab geeks solving crimes by finding DNA evidence and the like.

The success of that series spawned literally hundreds of imitators across the programming grid, many of which are still airing today. What’s more, the CSI-esque focus on crime-solving and evidence-gathering — as opposed to the personalities behind that process — has proven just as influential when it comes to “case of the season” shows, which focus on investigators trying to close a case over one or multiple seasons.

But go back to the first few seasons of CSI and you’ll find a show that looks a lot like The X-Files, with its focus on flashy imagery, cool blue aesthetics, and fascination with scientific processes. Even if Mulder and Scully proved to be incredibly well-developed characters, they, too, could often be boiled down to “the believer” and “the skeptic” — the kind of simplistic dichotomy that would beautifully suit many crime dramas that followed in its footsteps.

Second, the aesthetics of The X-Files expanded the notion of what TV was visually capable of. The X-Files took everything Twin Peaks had done and proved that other shows could do it too. You didn’t need to have a big-name Hollywood director like David Lynch to pull off such sharp cinematic sequences. You just had to budget the time and care to make those sequences matter. As you watch The X-Files, whether for the first time or the 50th, note how many of its scenes, especially its scary ones, are told entirely through visuals with spare dialogue. (David Chase, creator of The Sopranos, which would similarly break ground for visual storytelling on TV, was considering taking a job at The X-Files when HBO picked up The Sopranos.) More and more shows, both its contemporaries and otherwise, have been similarly emboldened.

Third, the serialized storytelling devices used by The X-Files have been copied by many genre dramas. The show mostly featured closed-off stories with a “monster of the week.” But many weeks, it instead gave itself over to a long-running story about aliens visiting Earth and working with assorted government officials, to shady and nefarious ends. Sure, it occasionally made no sense that Mulder and Scully could make huge shattering discoveries about a global conspiracy and then go right back to chasing urban legends down American backroads, but this oscillation between standalone tales and serialized adventures has driven many, many other dramas — mostly sci-fi, fantasy, and horror programs but also the occasional non-genre series, like CBS’s detective show The Mentalist.

Fourth, the series was critical of American foreign policy. While The X-Files was not the first series to question whether US efforts to win the Cold War had been worth many of our country’s dark deeds during that time, it was by far the most successful show to do so when it aired. Perhaps that is thanks to an accident of timing. The X-Files premiered, after all, in the wake of the Cold War’s end. Mulder and Scully might have been government functionaries, but their investigations usually uncovered just how horribly the US government had behaved — an undercurrent that has carried forward on everything from 24 (which often suggested the government’s bad behavior was, at best, necessary and, at worst, kind of awesome) to Homeland. (Funnily enough, Howard Gordon and Alex Gansa, both early X-Files writers, would go on to become writers and executive producers on 24, with Gordon eventually becoming the series showrunner. Gordon and Gansa also co-created Homeland, for which Gansa serves as the showrunner.)

Lastly, The X-Files mainstreamed modern paranoia. Forget simply modern television, which is full of conspiracy theories and cults and strange hidden secrets perpetrated by the government and shadowy corporations. Forget modern movies, which are full of the same. Instead, think of how much of our current political discourse is driven by a vague, never-proven suspicion that the US government is secretly colluding with [insert suspect entity here] to actively hurt its people.

It almost doesn’t matter if said paranoid suspicion is driven by actual evidence — as with the growing belief that the Trump campaign worked with Russian agents to influence the 2016 presidential election — or by some random person’s certainty that something bad must have happened — as with any number of conspiracies leveled against essentially every president of the last 25 years. (Though if you need an obvious example, consider the certainty that something bad had to have happened during the attacks on the US embassy in Benghazi, despite the fact that every investigation into the event turned up nothing criminal.)

The X-Files predicted this paranoid reality we all live in so skillfully that when it returned for its follow-up seasons in 2016 and 2018, it occasionally seemed as if the show had been lapped by the real world — impressive, considering this is a show in which a major plot point is the alien invasion of Earth.

But that prescience, above all else, is what makes returning to The X-Files 25 years after its debut so vital. The show has aged so beautifully (extremely rare for a TV show) because it plays less like an ultracool bit of TV stylishness and more like a mad prophet waving a warning flag to all of us gliding on past it. The world may keep changing. TV may keep changing. Humanity may keep changing. But what’s both remarkable and terrifying is how The X-Files keeps loping alongside us, never falling far enough behind for us to dismiss its dire predictions for the end of days.

Todd VanDerWerff is Vox.com’s critic at large. Monsters of the Week is available now.

Sourse: breakingnews.ie

0.00 (0%) 0 votes