Bitcoin is plummeting, with the price of a “coin” falling from a December high of $19,500 to $8,242 as of Tuesday morning.

The crash came a day after Wall Street got its own long-overdue correction: The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell by 4.6 percent on Monday, the worst point drop for the index ever.

Last year’s soaring Bitcoin prices led to a huge speculation frenzy, but now coin holders are rattled. Facebook is banning ads promoting Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, while banks including Citigroup, Bank of America, Capital One, and Discover have stopped Bitcoin purchases on credit.

Some Bitcoin enthusiasts and market analysts believe this is the start of a true crash, including Nouriel Roubini, a professor at New York University who is one of the world’s most well-known economists.

(HODL is Bitcoin lingo for “hold on for dear life,” referring to coin holders that don’t want to sell in hopes of a rebound.)

But others say the current decline is a typical seasonal event.

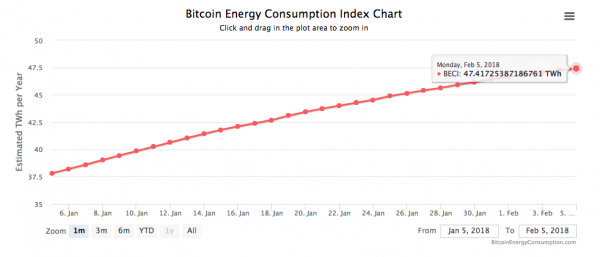

The drop in price, though, hasn’t had much of an effect on the massive amount of energy the Bitcoin network devours or its emissions. In fact, as of Tuesday, electricity consumption from Bitcoin rose to a record high of 47.4 terawatt-hours, according to Digiconomist, Alex de Vries’s Bitcoin analysis blog.

That’s roughly the energy used by all of Singapore, a country of 5.6 million people. It brings the rate of carbon dioxide emissions from Bitcoin up to 23.2 million metric tons per year. And it’s not showing any signs of slowing down.

Mining bitcoins — or verifying transactions to get coins — is a hugely energy-intensive process because of all the electricity needed for computational processing. About 80 percent of mining costs go toward electricity.

Unlike conventional currencies, there is no central bank or mint for Bitcoin that controls its value. Instead, the currency is managed through a distributed accounting system known as blockchain, and its value is governed purely by market forces.

Every Bitcoin user conducts transactions in a public ledger, but since that ledger is distributed across thousands of computers, it’s immensely tedious to reconcile and verify transactions across the network. Transactions are grouped together in blocks that require finding a cryptographic key to verify.

As I wrote last year, this process is like finding solutions to complicated math problems that become progressively more difficult. It’s a competitive process, with one miner receiving the award, currently 12.5 bitcoins, roughly every 10 minutes, so there’s a strong incentive to throw as much processor power — and thereby electricity — at the mining effort.

Or, as the Guardian’s Alex Hern wrote, it’s “a competition to waste the most electricity possible by doing pointless arithmetic quintillions of times a second.”

In Bitcoin’s early days in 2009, there were few computers, few transactions, and a price of $2 per coin, so mining was something you could do on your home computer.

Now with a global market cap of more than $122 billion, it demands specialized hardware called application-specific integrated circuit miners, and mining operations now use tens of thousands of these power-hungry boxes crammed into expansive warehouses to extract more coins.

And as the computations needed to verify transactions get more difficult, the corresponding coin award ratchets down. About 16.5 million bitcoins have been mined out of a theoretical cap of about 21 million, which may not be reached until 2040 at current rates of mining.

Most of the world’s bitcoin mining occurs in China, where miners have access to abundant cheap (and often dirty) electricity. The government of China is now starting to crack down on bitcoin trading, mainly to tamp down financial turmoil and not the environmental impact.

“Pseudo-financial innovations that have no relationship with the real economy should not be supported,” People’s Bank of China vice governor Pan Gongsheng wrote in a memo.

Some Chinese miners are now scouting sites in Canada for their mining operations to take advantage of cheap hydroelectric power, which would have the side benefit of shrinking the carbon footprint of their operations.

So why are people continuing to mine more bitcoin even as it becomes more difficult and its price goes down?

Because it’s still profitable.

In an email, de Vries explained that mining generates about $6.3 billion a year in revenue at current rates, but costs roughly $2.3 billion to run. That means the price of Bitcoin can drop by half and mining will still be a winning proposition.

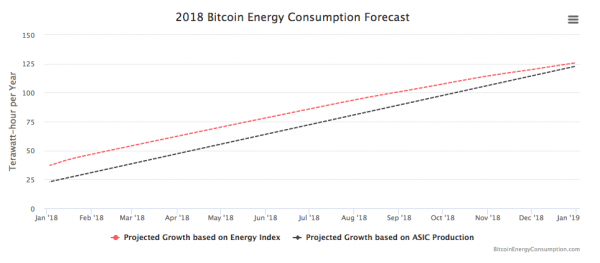

The extraordinary Bitcoin price surge in recent months has raced far ahead of the number of computers available to mine the digital currency. That means more specialized computers for mining are still being built, but it will take months to install enough hardware to catch up to demand.

As a result, Bitcoin’s electricity consumption could rise as high as 120 terawatt-hours by the end of the year, about as much as Norway and more than double its current appetite.

“Even with today’s price, the energy consumption could therefore still triple in the next year,” de Vries wrote. “It’s still very profitable to keep on producing more machines.”

Sourse: vox.com

0.00 (0%) 0 votes