When an officer of the Hoover Police Department in Alabama shot and killed Emantic Fitzgerald Bradford Jr., a 21-year-old black man, on November 22 at the Riverchase Galleria mall, the police claimed that Bradford had shot at least one person at the local mall prior to the police shooting.

But police have now admitted that Bradford didn’t shoot anyone, and arrested another man for the initial shooting. In the aftermath, the police shooting has drawn national attention as another example of an officer wrongly using deadly force against a black man.

Bradford did appear to have a gun. But he was licensed to carry a firearm, and it’s not illegal in Alabama to carry a gun in public.

According to police, some sort of altercation at the Riverchase Galleria on Thanksgiving night led to a shooting that injured an 18-year-old man and a 12-year-old girl, as well as the police shooting that killed Bradford.

Officials have repeatedly changed their story about the police shooting. They first said that Bradford was the initial shooter. They then acknowledged that Bradford wasn’t the shooter, but claimed that he “brandished” his gun. Most recently, they said Bradford had his gun out, but dropped the suggestion that he threatened anyone with it, CNN reported.

Bradford’s family says that Bradford was the victim of racial profiling. His mother, April Pipkins, told reporters that Bradford was, if anything, trying to protect people from the actual shooter. The family’s lawyer, civil rights attorney Benjamin Crump Jr., claims that eyewitnesses said Bradford was trying to get people away from the initial shooting, and that Bradford kept his gun in his waistband.

The officer “saw a young black man with a gun and he shot him,” Crump told reporters.

An autopsy commissioned by the family found that Bradford was shot three times in the back.

Bradford had no criminal record, and he was honorably discharged from the Army, Crump said.

The Alabama Law Enforcement Agency is investigating the shooting, and the Hoover Police Department is conducting an internal investigation. Police have not revealed the identity of the officer who shot Bradford, who’s on administrative leave as the investigation proceeds.

Bradford’s family is demanding transparency in the investigation, including the release of any video. The family has also asked for city officials to apologize for mistakenly identifying Bradford as a shooter.

The shooting led to protests outside the mall. And it’s received national attention as police use of force, particularly against black Americans, continues drawing heightened scrutiny — due to vast racial disparities in police use of force.

Black people are much more likely to be killed by police than their white peers

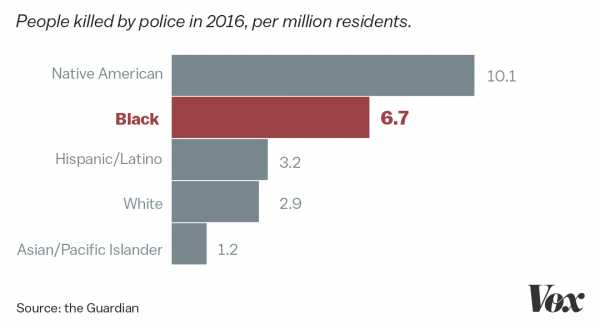

Based on nationwide data collected by the Guardian, black Americans are more than twice as likely as their white counterparts to be killed by police when accounting for population. In 2016, police killed black Americans at a rate of 6.66 per 1 million people, compared to 2.9 per 1 million for white Americans.

There have also been several high-profile police killings since 2014 involving black suspects. In Baltimore, Freddie Gray died while in police custody — leading to protests and riots. In North Charleston, South Carolina, Michael Slager shot Walter Scott, who was fleeing and unarmed at the time. In Ferguson, Darren Wilson killed unarmed 18-year-old Michael Brown. In New York City, NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo killed Eric Garner by putting the unarmed 43-year-old black man in a chokehold.

One possible explanation for the racial disparities: Police tend to patrol high-crime neighborhoods, which are disproportionately black. That means they’re going to be generally more likely to initiate a policing action, from traffic stops to more serious arrests, against a black person who lives in these areas. And all of these policing actions carry a chance, however small, to escalate into a violent confrontation.

That’s not to say that higher crime rates in black communities explain the entire racial disparity in police shootings. A 2015 study by researcher Cody Ross found, “There is no relationship between county-level racial bias in police shootings and crime rates (even race-specific crime rates), meaning that the racial bias observed in police shootings in this data set is not explainable as a response to local-level crime rates.” That suggests something else — such as, potentially, racial bias — is going on.

One reason to believe racial bias is a factor: Studies show that officers are quicker to shoot black suspects in video game simulations. Josh Correll, a University of Colorado Boulder psychology professor who conducted the research, said it’s possible the bias could lead to even more skewed outcomes in the field. “In the very situation in which [officers] most need their training,” he previously told me, “we have some reason to believe that their training will be most likely to fail them.”

Part of the solution to potential bias is better training that helps cops acknowledge and deal with their potential prejudices. But critics also argue that more accountability could help deter future brutality or excessive use of force, since it would make it clear that there are consequences to the misuse and abuse of police powers. Yet right now, lax legal standards make it difficult to legally punish individual police officers for use of force, even when it might be excessive.

Police only have to reasonably perceive a threat to justify shooting

Legally, what most matters in police shootings is whether police officers reasonably believed that their lives were in immediate danger, not whether the shooting victim actually posed a threat.

In the 1980s, a pair of Supreme Court decisions — Tennessee v. Garner and Graham v. Connor — set up a framework for determining when deadly force by cops is reasonable.

Constitutionally, “police officers are allowed to shoot under two circumstances,” David Klinger, a University of Missouri St. Louis professor who studies use of force, previously told Dara Lind for Vox. The first circumstance is “to protect their life or the life of another innocent party” — what departments call the “defense-of-life” standard. The second circumstance is to prevent a suspect from escaping, but only if the officer has probable cause to think the suspect poses a dangerous threat to others.

The logic behind the second circumstance, Klinger said, comes from a Supreme Court decision called Tennessee v. Garner. That case involved a pair of police officers who shot a 15-year-old boy as he fled from a burglary. (He’d stolen $10 and a purse from a house.) The court ruled that cops couldn’t shoot every felon who tried to escape. But, as Klinger said, “they basically say that the job of a cop is to protect people from violence, and if you’ve got a violent person who’s fleeing, you can shoot them to stop their flight.”

The key to both of the legal standards — defense of life and fleeing a violent felony — is that it doesn’t matter whether there is an actual threat when force is used. Instead, what matters is the officer’s “objectively reasonable” belief that there is a threat.

That standard comes from the other Supreme Court case that guides use-of-force decisions: Graham v. Connor. This was a civil lawsuit brought by a man who’d survived his encounter with police officers, but who’d been treated roughly, had his face shoved into the hood of a car, and broken his foot — all while he was suffering a diabetic attack.

The court didn’t rule on whether the officers’ treatment of him had been justified, but it did say that the officers couldn’t justify their conduct just based on whether their intentions were good. They had to demonstrate that their actions were “objectively reasonable,” given the circumstances and compared to what other police officers might do.

What’s “objectively reasonable” changes as the circumstances change. “One can’t just say, ‘Because I could use deadly force 10 seconds ago, that means I can use deadly force again now,’” Walter Katz, an attorney who specializes in oversight of law enforcement agencies, previously said.

That is the constitutional standard. There are also different criminal standards at the state level, which may have different interpretations for what is reasonable use of force and what isn’t. But, broadly, police officers are allowed to use force if they reasonably perceive a threat even if a threat is not actually present.

In general, officers are given a lot of legal latitude to use force without fear of punishment. The intention behind these legal standards is to give police officers leeway to make split-second decisions to protect themselves and bystanders. And although critics argue that these legal standards give law enforcement a license to kill innocent or unarmed people, police officers say they are essential to their safety.

For some critics, the question isn’t what’s legally justified but rather what’s preventable. “We have to get beyond what is legal and start focusing on what is preventable. Most are preventable,” Ronald Davis, a former police chief who previously headed the Justice Department’s Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, told the Washington Post. Police “need to stop chasing down suspects, hopping fences, and landing on top of someone with a gun,” he added. “When they do that, they have no choice but to shoot.”

Police are rarely prosecuted for shootings

Police are very rarely prosecuted for shootings — and not just because the law allows them wide latitude to use force on the job. Sometimes the investigations fall onto the same police department the officer is from, which creates major conflicts of interest. Other times the only available evidence comes from eyewitnesses, who may not be as trustworthy in the public eye as a police officer.

“There is a tendency to believe an officer over a civilian, in terms of credibility,” David Rudovsky, a civil rights lawyer who co-wrote Prosecuting Misconduct: Law and Litigation, previously told Amanda Taub for Vox. “And when an officer is on trial, reasonable doubt has a lot of bite. A prosecutor needs a very strong case before a jury will say that somebody who we generally trust to protect us has so seriously crossed the line as to be subject to a conviction.”

If police are charged, they’re very rarely convicted. The National Police Misconduct Reporting Project analyzed 3,238 criminal cases against police officers from April 2009 through December 2010. They found that only 33 percent were convicted, and only 36 percent of officers who were convicted ended up serving prison sentences. Both of those are about half the rate at which members of the public are convicted or incarcerated.

The statistics suggest that it would be a truly rare situation if the officers who shot and killed Bradford were convicted of a crime.

Sourse: breakingnews.ie

0.00 (0%) 0 votes