In October 2017, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin forecast that “the stock market will go up higher” if Republicans passed a tax cut bill.

Both the S&P 500 and Dow Jones Industrial Average are now down from where they were on December 22, 2017, when President Donald Trump signed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The S&P 500 closed the day Monday at its lowest level since October 2017.

In September 2017, Mnuchin said that not only would the GOP’s tax plan “pay for itself, but it will pay for the debt.” He also claimed it would “cut down the deficits by a trillion dollars.”

In October 2018, Treasury said the United States’ federal budget deficit had increased to $779 billion in fiscal 2018, up 17 percent from the year before.

For one thing, Mnuchin should probably stay out of the prediction business. But beyond that, given that it’s been a year since the TJCA passed, it’s probably a good time to take stock of what it has — and hasn’t — done for the US economy, markets, businesses, and workers.

The 2017 tax bill cut taxes for most Americans, including the middle class, but it heavily benefits the wealthy and corporations. It slashed the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, and its treatment of “pass-through” entities — companies organized as sole proprietorships, partnerships, LLCs, or S corporations — will translate to an estimated $17 billion in tax savings for millionaires this year. American corporations are showering their shareholders with stock buybacks, thanks in part to their tax savings.

There’s a lot about the effects of the tax cuts that we still don’t know and may never — the economy doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and myriad factors affect what happens to it. But a lot of the immediate stimulus effects of the bill are probably already here, and the longer-term ones will be harder to spot. Enough time has passed to evaluate some of the bill’s impact and whether promises made about it were kept.

“We are not seeing the kind of broadly shared growth overall that a lot of the proponents of the law were hoping for,” Alison Omens, the managing director at Just Capital, a nonprofit that measures and ranks American companies on social responsibility, said.

The tax bill has boosted economic growth … probably temporarily

The tax cuts have juiced economic growth and, combined with increased government spending, injected a one-time jolt into the US economy. But that’s not going to last forever — or maybe even past next year.

Gross domestic product growth was an estimated 4.2 percent in the second quarter of this year, and it was 3.5 percent in the third quarter. But most economists agree those numbers aren’t sustainable on an extended basis.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that GDP growth, spurred by fiscal stimulus including the tax cuts and increased government spending, will be 3.1 percent in 2018 and will decline to 2.4 percent in 2019 as business investment and government purchases slow.

It then projects that GDP growth will slow further to 1.6 percent each year from 2020 through 2022 and 1.7 percent annually from 2023 to 2028.

“We went out and borrowed money and used that to cut everyone a check, and much of that was spent,” Mark Zandi, the chief economist with Moody’s Analytics, said.

Business fixed investment — the investment in physical assets like property and equipment — was up in the first and second quarters of the year but was flat in the third quarter, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Manufactured durable goods shipments decreased for the third time in four months in November, and shipments fell after two months of increases.

Doug Holtz-Eakin, an economist with the conservative-leaning think tank the American Action Forum, said weak investment could be a “blip” but that it is cause for concern. He also noted that CEO confidence is coming down, though that is likely driven by other factors, such as Trump’s trade aggressions.

The tax bill hasn’t paid for itself

Multiple Republicans claimed that the tax cuts would pay for themselves by way of what most economists say were unrealistic claims of economic growth.

“I think this tax bill is going to reduce the size of our deficits going forward,” Sen. Pat Toomey (R-PA) told reporters last year.

That’s not what happened.

“It was implausible on its face when it was said, and we have no evidence that changes that view,” said Alan Auerbach, the director of the Robert D. Burch Center for Tax Policy and Public Finance at UC Berkeley. “What we would have needed for this thing to pay for itself is implausibly large growth, and that just didn’t happen.”

As mentioned, the Treasury Department said that the federal budget deficit for fiscal year 2018, ending in September, had increased 17 percent to $779 billion. The government saw a $305 billion deficit in October and November this year, a significant jump from the $202 billion it saw in the same period last year. The federal deficit is projected to hit $1 trillion in fiscal year 2019.

The CBO estimated in April that tax bill would add $1.9 trillion to the debt over the course of a decade.

“In terms of the big picture, what it’s doing is making current rich people better off at the expense of lower-income households and future generations,” William Gale, a senior fellow in economics studies at think tank the Brookings Institution, said.

He described the tax bill as the “wrong thing” — legislation that disproportionately benefits the wealthy and corporations — at the “wrong time,” because it was an attempt to deliver fiscal stimulus when the economy was already strong and it might have been a better idea to try to address the debt.

Gale quoted former President John F. Kennedy: “The time to repair a roof is when the sun is shining.”

The tax bill has delivered a windfall to corporate America

Not only did the tax cuts slash the corporate tax rate to 21 percent from 35 percent, but it also contained a one-time “repatriation holiday” that allowed companies to bring back earnings stashed abroad at a significantly reduced tax rate from the 35 percent they otherwise would have owed. Since then, companies with trillions of dollars abroad have started to bring that money back. Zandi, from Moody’s, described it as a “helicopter drop of money.”

What that means for the broader economy, however, depends what companies do with it.

It appears that a lot of the windfall is going to rewarding corporate shareholders by way of stock buybacks, where companies repurchase their own shares from the marketplace and leave remaining shareholders with a bigger chunk of the company and, therefore, greater earnings per share.

Stock buyback announcements surpassed $1 trillion for the first time ever this year, according to the investment research firm TrimTabs. Apple, which had about $250 billion in unrepatriated cash pre-tax bill, in May announced a $100 billion stock buyback.

The tax bill hasn’t quite translated to an increase in the stock market, at least not over the course of the year. While in late 2017 and early 2018, US stocks rallied, the markets have since become rockier, and major indexes have given back their post-tax bill gains. Given who tends to own equities, stock market indices are more a measure of wealthy people’s well-being than of the rest of the population.

“That was a one-time boost that evaporated,” Zandi said.

There is some tension between the increase in stock buybacks and the fact that it hasn’t led to a major increase in stock prices. Of course, there’s much more that goes into the stock market’s performance than the tax bill and buybacks — at the current moment, for example, trade fears and the threat of rising interest rates from the Federal Reserve.

Companies still presumably have time to use the cash from the repatriation holiday to invest more in operations, new projects, and workers, but if recent history is any guide, it might be unlikely to happen. The last time Congress approved of a repatriation holiday in 2004, most of that money went back to shareholders. And after the George W. Bush administration cut taxes on dividends in 2003, one study shows it increased financial payouts to shareholders but “caused zero change in corporate investment” and had “no impact on employee compensation.”

The tax bill didn’t bring a definitive boost for workers

What appears not to have happened — at least not on a broad scale — is for companies to have transferred their tax gains into a significant benefit for workers.

There were a handful of high-profile bonus and wage announcements after the tax bill was passed, but it’s not clear that tax cuts have delivered some major boon to the US labor force. The left-leaning Economic Policy Institute recently estimated that bonuses gave workers 2 cents more per hour over the past year.

The Wall Street Journal in October pointed to various surveys suggesting most companies aren’t passing on their tax savings to employees. A survey of 152 companies by the recruitment firm Korn Ferry International found that 14 percent of companies were using their tax cuts to increase base salaries, and a poll of 1,500 companies from the consulting firm Mercer LLC found that 4 percent are putting their tax money toward paying employees.

An analysis from Just Capital of 145 publicly traded companies found that 6 percent of tax-related savings was going to workers, while 56 percent was going to shareholders.

“There’s clearly not enough rent sharing despite a couple of high-profile announcements,” Kimberly Clausing, a professor of economics at Reed College, told me. “I don’t think that mechanism would have been strong, and we certainly would have seen it by now if it existed.”

That’s not to say that the labor market is bad — the unemployment rate is 3.7 percent, and the US has been adding jobs gradually since the recession. The pace of wage growth is improving, with wages increasing 3.1 percent year-over-year in both October and November, but taking inflation into account, much of that is wiped out.

And the tax cuts could deliver more benefits to workers down the line. The argument is that it takes time for companies to invest more in their businesses, and if they do, that will increase worker productivity, which will lead to gains for workers.

Clausing and Edward Kleinbard, a law professor at the University of South Carolina and former chief of staff for the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation, in an October 2017 Vox piece pointed to evidence that a drop in corporate tax rates might not increase wages, noting that after corporate tax rates were reduced in the UK, wages were too.

Holtz-Eakin told me that getting better sustained productivity that translates to higher wages and a higher standard of living is a sort of “holy grail” in tax cuts such as this one, but it’s “genuinely too soon to know” what will happen.

Time will tell how this all pans out … sort of

Part of the issue with deciphering what the tax cuts have and haven’t done is that it’s not as though the US economy, wages, or the stock market are only swayed by one factor. The same CEOs who were excited about the Trump tax cuts are less than thrilled with his trade war.

There is a chance that more obvious benefits of the tax cuts are still on the horizon — say, for example, if Americans get more money back from the IRS come tax season in April 2019. (Of course, it could go the other way, and they could get less.) And the tax law’s effects are still playing out in other sectors, such as health care, given that the bill scrapped Obamacare’s individual mandate, and housing, with a provision for tax breaks for developers in low-income zones. Moreover, many of the provisions in the 2017 tax cut bill, including individual tax changes, will expire between now and 2026.

“Having more years to observe the economy as other conditions change might be helpful,” Auerbach said, though he clarified, “When you’re looking at the overall performance of the economy or a broad sector like business investment, in any given year, there are always going to be many things going on.”

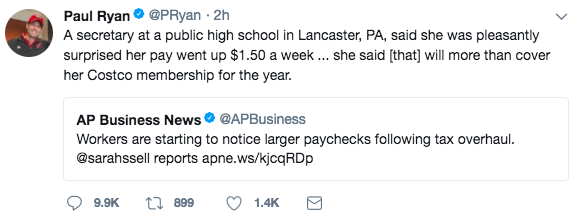

Weighing it all out, it seems clear the Republican tax cuts haven’t been the winner for everyday Americans many in the GOP promised. It is true that most people have more money in their pockets, but corporations and the wealthy are carrying a much larger chunk of change than the extra $1.50 per paycheck House Speaker Paul Ryan bragged about a school worker getting to help cover her Costco membership.

“We could certainly use tax reform,” Gale said. “But there’s no reason why tax reform needs to lose money or benefit the rich at the expense of the poor.”

Sourse: breakingnews.ie

0.00 (0%) 0 votes