After a couple of weeks of media narratives dominated by economic pessimism, the Bureau of Labor Statistics weighed in Friday morning with a monthly jobs report that is chock full of good news.

Employers added 312,000 new jobs in December — an excellent number this late in an economic recovery cycle — and revisions to the past two months’ worth of data showed 58,000 more additional jobs. The unemployment rate, while still low, bounced up slightly to 3.9 percent, which is actually probably good news because it shows that people continue to reenter the labor force at a rapid clip as the labor market improves.

Average hourly wages rose 3.2 percent over the course of the year, which, while not exactly spectacular, is the best number we’ve seen since the Great Recession.

All in all, it’s both a good report and one that’s comfortingly normal.

Wage growth has been slow for the past few years despite the low unemployment rate, but the trend is toward faster wage growth — and the faster wage growth is tempting more people into the workplace. There doesn’t appear to be anything profoundly “broken” about the labor market other than the fact that there was a huge recession from 2008 to 2009, a slow recovery from 2010 to 2015, and then a Federal Reserve that’s been slightly too eager to throw in the towel and proclaim the arrival of full employment ever since.

And speaking of the Fed, the only black fly in the chardonnay here is that this report is likely to increase tensions between the White House and America’s central bank.

The Fed’s general mentality has been that it wants to raise rates as quickly as it can manage to safely pull off, and a strong jobs report will be taken as vindicating the claim that it is safe to continue raising rates. Trump wants the Fed to keep rates low, primarily to respond to a choppy stock market that is strongly impacted by economic problems abroad.

People like me who’ve been consistently opposing rate increases no matter who is president (Obama-era take, Trump-era take), meanwhile, can point to the fact that the labor force keeps growing as evidence that the Fed should ignore the unemployment rate and assume there are still plenty of potential workers out there.

The economy has room to grow

The simple argument against the idea that the low unemployment rate means we have a super-strong economy is to look at the share of prime-age workers — people between the ages of 25 and 54 — who have jobs. By this measure, the economy is doing okay but by no means great. We’re still a bit below the 2007 peak, which itself was well below the level we achieved in 2000.

If you look at younger people, the case that there are more workers available looks even stronger — the current number is well below where it was in 2007, which itself was below 2000, which in turn was not the all-time high point.

Some of this, of course, is people going to school, which is a perfectly healthy development.

But we know that many students also work at least part time while they’re in school and that college tuition has gotten a lot more expensive. We also know that much of the recent growth in college attendance has come from low-quality programs (often run for profit) that have low completion rates and tend to leave students saddled with debt that is difficult for them to pay off.

So it seems wrong to consider the long-term decline in youth employment to be an entirely benign structural development driven by an increased love of schooling. At least some of the increase in schooling seems to be driven by young people pushed into low-quality educational options because the underlying job market has been difficult.

Further evidence of labor market weakness is that right now, wage growth — though certainly not terrible — is “meh” rather than “amazing,” as employers continue to find it not so hard to find workers to hire. The latest report saw the fastest wage growth since the arrival of the Great Recession, which is simply another way of saying that we are finally back to a wage growth level that was considered normal before the recession lowered our standards.

These signs of ongoing labor market weakness raise the question of why exactly there’s so much rush to raise interest rates. It’s true that the economy is no longer deeply depressed and we don’t urgently need low rates. But is there some reason we need higher rates?

Inflation is not a problem

Low interest rates are, fundamentally, pretty nice. If you need a loan to buy a house or a car or a major appliance, you can get one for cheap. If your business needs a loan to expand its office space or obtain more business equipment, you can get one for cheap. And those cheap durable goods and business investments aren’t just pleasant for the people who directly buy them; they also boost output and employment throughout the economy.

The reason you don’t just keep rates low forever is that too much easy money will lead to inflation.

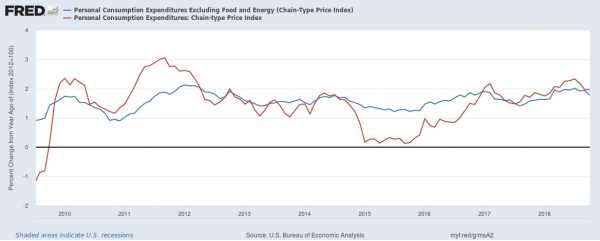

But there’s no actual inflation problem in America today. The Fed is supposed to be targeting a 2 percent inflation rate, but once you strip out the price of volatile food and energy commodities, inflation has been consistently lower than that.

Of course, normal people care about food and energy prices too, and when they’re included in the mix, inflation has sometimes popped above 2 percent. But with these volatile commodities included, inflation has also tumbled well below 2 percent. Right now “core” inflation (the blue line) is not only slightly below 2 percent but is actually falling.

So it’s not really clear what the emergency is. Or perhaps more to the point, it raises the question of whose interests are really served by a determination to, in effect, fight inflation preemptively.

Labor scarcity is good for workers

The basic mechanism by which excessively easy monetary policy sparks inflation is supposed to be something like this: Faced with an acute shortage of workers, wages will start to rise faster than underlying productivity. Employers will thus have to raise prices to compensate for the higher pay, wiping out workers’ wage gains and leading to more demands for pay increases. The cycle simply continues, or even intensifies, devastating people with fixed incomes and ultimately wreaking havoc on investment decisions.

But as Binyamin Appelbaum recently argued in the New York Times, another thing that can happen when workers get pay raises in excess of productivity growth is that workers’ share of the national income pie grows. Instead, the trend in the 21st century has been for workers’ share to consistently decline as the economy has suffered through two recessions and zero periods of really strong labor markets.

Right now, unemployment is low and wages are rising.

Perhaps the Fed should just let them keep on rising for a bit, hoping that wage hikes will eat away at profit margins rather than spark inflation. Viewed through this lens, the determination to raise interest rates before inflation materializes looks more like a ploy to guarantee shareholders’ profits than an effort to stabilize prices.

At the very worst, an experiment with extended low interest rates could lead to a little inflation, and then the Fed could raise interest rates. But at its best, it could have broad structural benefits that go beyond a quirk burst in pay.

Imagining maximum employment

For the sake of convenience and clarity, economists like to conceptually separate “cyclical” economic issues (unemployed workers, idle machines, etc.) from “structural” ones (education and skill levels, the size of the working age population, etc.).

Reality, however, is messier than that.

Currently, for example, ex-convicts and the long-term unemployed face fearsome barriers to getting a new job that wouldn’t necessarily be a problem for a newly minted high school graduate. But a strong “cyclical” recovery that produces labor force shortages and pushes employers to take risks on reentering prisoners or people who’ve been jobless for years ends up being a “structural” remedy to the problem since, having been hired once, people are no longer on the margins of the labor force and are now capable of participating in a mainstream way.

Similarly, when forced to do so by strong cyclical pressures, employers may find ways to better accommodate workers with disabilities. Engaging in racial discrimination becomes more costly during a spell of full employment, and managers inclined to do it will find themselves falling by the wayside in favor of those ready to give opportunities to black and Latino workers.

More fundamentally, while in a weak labor market, the in-demand management skill is how to squeeze workers a little harder, in a strong labor market, skill at providing on-the-job training could become a hot management trend.

By the same token, prolonged labor market weakness has created a situation in which lots of people are employed in fundamentally low-value forms of labor. There’s been a huge proliferation of various kinds of on-demand delivery apps (for laundry, food, booze, etc.) that leverage a little bit of technology to connect consumers with low-productivity, low-paid irregular labor. In a hot labor market, those workers will transition into more normal jobs, and the technology workers making these apps will end up reemployed to solve more socially and economically profound problems that genuinely raise productivity rather than finding new ways to exploit loopholes in minimum wage rules.

Up from Trumpism

None of this is to say, obviously, that Trump has personally thought through all these issues or familiarized himself with the charts and graphs that could make the case for low interest rates persuasively. (I am, of course, happy to share even more charts with him if he’d like a briefing.)

But Trump’s willingness to openly campaign for lower rates and more economic growth against the central bank’s institutionalized conservatism is an example of a situation where breaking norms can be a good idea.

Barack Obama simply wouldn’t have done something like this, even though at times, his economic team believed that a more aggressive Fed would be good for the country. Yet while the norm of strong deference to central bankers appeared to make sense in the wake of the inflation of the 1970s, workers’ genuinely bleak experience with the 21st-century labor market really ought to have prompted a reevaluation of the thinking around these issues.

A systematic inflationary bias would be a bad way to do economic policy, but a systemic disinflationary bias is also bad. Paranoia about letting the unemployment rate get “too low” even in the absence of any actual inflation problem is a huge thumb on the scales in favor of incumbent business owners and against workers and innovation.

The next president shouldn’t imitate Trump’s slipshod opportunism, but the idea of pushing aggressively for growth-oriented monetary policy makes a lot of sense. And the fact that the gods of central banking haven’t come down from the sky to smite Trump for his impertinence ought to encourage future boldness.

Sourse: breakingnews.ie

0.00 (0%) 0 votes